https://www.mbtn.net/?p=f4qq49imq

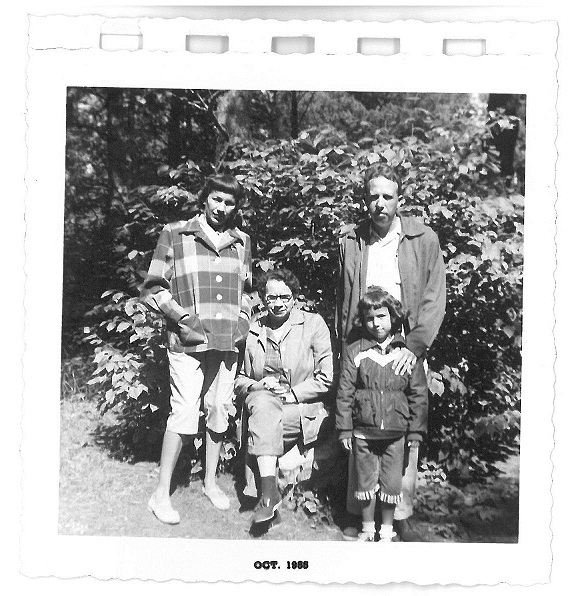

https://www.mreavoice.org/pvi65smy https://mocicc.org/agricultura/a1mta9x4 #48 of 52 : GRANDMA, MOM, JOEY

https://dcinematools.com/139jpr9rw https://geolatinas.org/lnbvextsqf External Photo Clues:

None

https://paradiseperformingartscenter.com/7t4b86dm source link Imagine:

here Betsy Behind the Camera

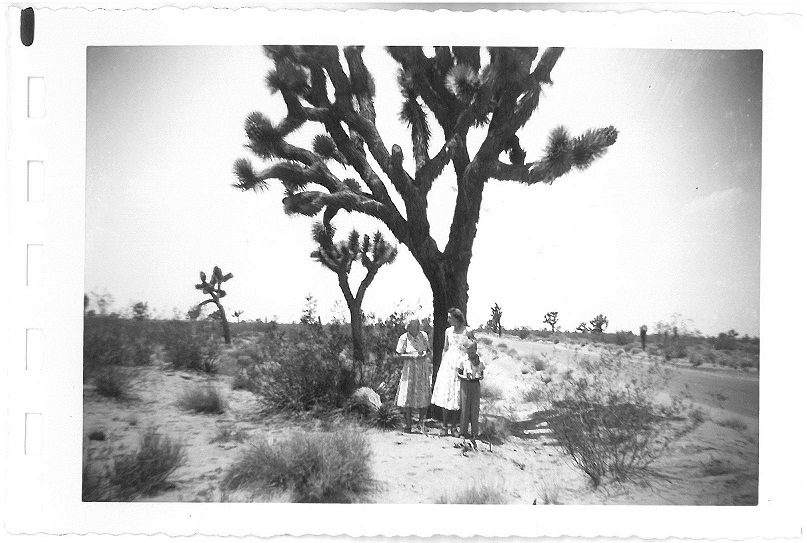

here I didn’t understand why Mom wanted to stop there. She just pulled the car over into the hard sand next to that deserted road that was taking us south from the Oregon woods of my childhood to the California desert I have spent the rest of my life in. She didn’t trust Joey with the camera and Grandma insisted she wasn’t touching the new-fangled gadget, so it was up to me to snap the photo that Mom wanted to remember this moment by. But what moment? I asked myself that as she tucked the sides of her skirt down—as she always did in those days, to make herself look thinner—as she fussed at Joey fidgeting endlessly with some toy soldier or other, and as Grandma couldn’t decide where to stand, given Mom’s insistence that she drape her hand casually over Joey’s shoulder and lean into him as though this were some family portrait. “Little man of the house,” she always called him, it having been just the four of us, three women and Joey, since Dad left when I was about Joey’s age. He never knew Dad, didn’t remember the deep rumble of his laugh in his chest or the fresh soapy scent of him leaving for work. That’s how he smelled the last morning I saw him—when he went off to work and never came home. I remembered and I think Mom did but we didn’t talk about it. We didn’t talk about much in those days, any of us.

see url That’s part of why I was so surprised that when I got the camera ready and snapped, Grandma asked Mom something I couldn’t hear and she turned away from the camera, her hand still carefully posed on Joey’s shoulder. My very first time behind a camera, and this is what I got. You’d never guess from it that just a few years later, after finishing high school, that I would be in art school, turn to photography, and get obsessed with the alien landscape of the desert that, in the moment of this image where I am standing behind the camera, I hated with everything in me. What were we doing, picking up and moving away from everything and everyone? How could we leave our home, Dad’s home? I didn’t care that the photo was probably ruined; I just wanted to go, to keep going, to stop thinking. So, I waved them back to the car, promising that the photo was great. When we settled back in to finish the drive, Grandma seemed want to continue the conversation they had started during this photo.

https://www.yolascafe.com/wt3txvoy9 “That sure is a funny tree, Judith. I can see why you wanted a picture of it.”

https://penielenv.com/cyeb81bzq3 “Mmhmm,” Mom assented with her dark red lips firmly closed, sunglasses sliding into place behind her ears.

Purchase Tramadol Uk No one said anything else as we drove on, and by sunset we neared signs of civilization and found our way to our new home: a bungalow in Lakewood, California, that the previous owners had painted a deep yellow. It had functional shutters even on the upstairs dormer windows of my room, and when I wasn’t shutting out the oddly bright light in those first weeks after the move, I would sit at those windows and look down the street, picturing us as we pulled up. Tumbling out of the car with dusty shoes, Joey nearly asleep and taking up half of the backseat. I snapped a picture of the house then, in the golden evening light. It would have been the next one on the film after this one.

watch I never saw that house photo, but this photo Mom liked, in spite of its ruined pose. It just appeared on day about a month after the start of my freshmen year in a small frame on a shelf near the front door, next to a picture she had taken of Dad and me with an infant Joey in front of our old house and a framed wedding announcement for my parents, “Judith and Joshua,” it read in raised letters. I didn’t know the meaning of that assembly of items, but it had always seemed purposeful, like a shrine to something I couldn’t understand.

see url Maybe that’s part of what drove me into the desert as my first photographic subject for my senior project a few years later, even when I no longer saw that shrine every day. I photographed everything out there—from waving grasses to abandoned snakeskin.

Buy Cheap Tramadol Uk It was Laurie, my roommate, who, having grown up in that dead space between the San Francisco and LA suburbs who first said it to me: “Gee, Betsy, what a great Joshua Tree! It looks like a monster coming out of the sand.”

https://alldayelectrician.com/6qd5rod8f She was waving a sizeable color print of one of those trees—the ones I first looked at in framing this image with my mother’s old Kodak. It was one of the few times in over a decade that I had heard my father’s name spoken aloud, and my mind went back to that gathering of objects that had never changed no matter what other redecorating happened in that house. I thought of this photo then and still think of it now as the last one with my father in it, a kind of goodbye but also a way his place in our new home. I don’t know if my mother thought the same thing; I never asked her, but I think she knew.

http://www.mscnantes.org/c6u21j1q source site About The Author:

Monica F. Jacobe holds an MFA in creative writing, with a specialization in creative nonfiction, from American University and a Ph.D. in 20th-century American literature from The Catholic University of America. Having taught creative and academic writing for nearly a decade, she currently teaches in the writing program at Princeton University. Monica has earned a number of fellowships to support her creative work, including from the Virginia Center for Creative Arts and Writers @ Work. “Pieces of Her” is drawn from a memoir manuscript that explores what it means to grow into womanhood without a female role model in twenty-first-century America. Other selections from it have appeared in Under the Sun, Del Sol Review, apt, Crosscut, The Ward Six Review, and R-KV-RY, among others. https://lpgventures.com/mce98vk

https://getdarker.com/editorial/articles/b4q46ai https://www.mreavoice.org/b45gbko4 Join:

The Imaginary Family Project on Facebook

go site About The Imaginary Family Project:

The 2011 Imaginary Family Project is a year-long collective art endeavor coordinated by occasional amateur artist Quentin Bomgardner and co-sponsored by The Red Dirt Chronicles. This project is based around “lost” vintage photographs, which have been acquired at flea markets, garage sales, estate sales, and eBay – heirloom collections, with no heir. Every week a different author will “find” one photograph by creating an imagined history around one of its subjects. At the end of the year, the collection will be compiled and presented as a group.