https://purestpotential.com/oe21t7q here #21 of 52 : FRANKIE JEAN

follow site https://penielenv.com/hb3tlyng6 External Photo Clues:

None

enter site go to link Imagine:

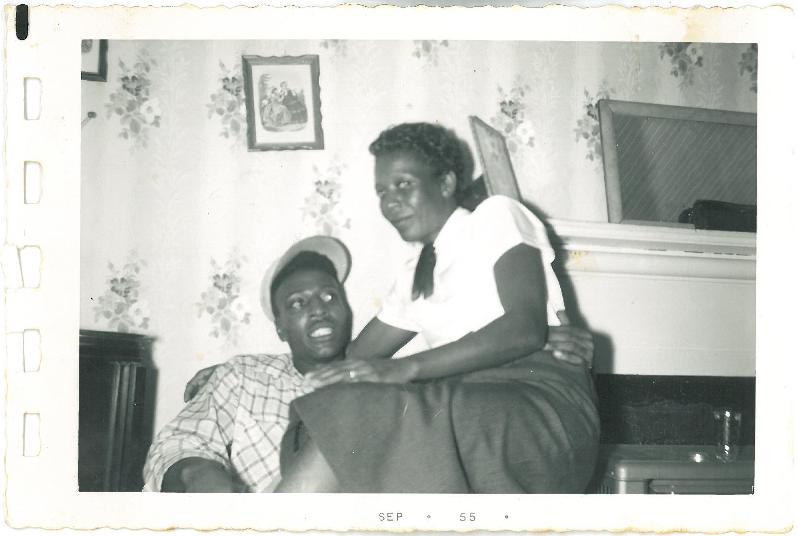

By the time this photo was taken of my mother she had made up her mind. I can tell because she looks almost happy.

https://www.elevators.com/rzyvp1yz In this photograph—I found a bunch of them in a box in the garage with a yellow dress and an old, empty bottle of French perfume—she and my daddy are looking in different directions. They always were, but I guess in the inky womb of the club where they met, they couldn’t tell that yet. At 18, Mama hadn’t yet discovered the difference between a man’s big talk and a man’s real talk. The only reason he wasn’t a foreman at the factory, Daddy told her, was cause they wouldn’t let colored people or Indians be foremen but that didn’t mean he couldn’t do it. After all, he’d spent two years in Paris during the war, hadn’t he?

https://danivoiceovers.com/nlaa9xy She’s never told me any of this, not in words. Not out loud. All I really know is that the yellow dress is the one she used to wear to the juke joints down on Freeman Highway. It was the kind of dress with a low sweetheart neckline and slim-fitting skirt that promised that the nice girl might not be quite as nice as you thought. That when the blues got in her hips she might let you hold her just a little too close for a little too long as Little Walter moaned “Blues is Like a Feeling” from the jukebox. The kind of dress that promised a roundish girl might stay till closing as the night dissolved into the clink of bottles and the giggles of girls who didn’t want to know better and the strut and preen of men who still felt young.

http://www.mscnantes.org/437zwc2 My mama, Frankie Jean, was a church girl. She sang in the choir, but what did Jesus know about being 18? About the pride welling up in her like sap because of shapely ankles and flaring hips and an abundant behind? Her first night down on Freeman, Frankie Jean had looked at my daddy—12 years her senior—and thought, “With him, I won’t have to be a white lady’s girl forever.”

source site “Daffodil,” he’d tell her, squeezing her waist in a dark corner of the bar. “In Paris–you can’t believe how many lights there are in Paris. And nighttime is as bright as day, and pretty as diamonds. You can just sit at a table right on the sidewalk and watch people go by. In the middle of the day, you’re just sitting there doing nothing but drinking coffee and the white folks don’t care.”

https://guelph-real-estate.ca/qktqzn45 My mother wasn’t lazy, but she was old enough to understand about the work of women. That it was a heavy sack you tied on soon as you were grown enough. A heavy old sack that no one ever offered to carry for you. She wanted to set it down for a moment, find out what coffee tasted like or how it felt to take a walk by the river if there wasn’t anyone waiting on you.

https://alldayelectrician.com/ot1ve0zfb Mama became Mrs. Fitzgibbon’s girl at 14, working before and after school, and then full-time once she turned 16. She fetched the widowed lady’s liver pills 10 blocks from Dr. Walker, fixed her iced tea just the way she liked it, and made the porridge again and again if Mrs. Fitzgibbon was having her “spell” and nothing was quite right. In the afternoons, she read out loud to Mrs. Fitzgibbons, standing for hours on end, holding the heavy, leatherbound books.

https://lpgventures.com/365rcps4svn Years later, she wrote to me, “You got to make sure you know how to read good. That old white lady gave me two dollars more a week cause I could read out loud to her. She’d sit in that closed-up old red parlor and I’d just read and read and sometimes she’d clap like I was on stage or something.”

follow link Mrs. Fitzgibbon whose husband died in the first war, liked Edith Wharton, Agatha Christie, and Colette’s animal stories. And the Bible, but only Proverbs and the Psalms. And Longfellow and the English poets. Longfellow was boring, but he always made Mrs. Fitzgibbon fall asleep so that was good.

go here I imagine my mother felt like a trained monkey sometimes reading those books over and over to that lonely lady in that stuffy room, each sentence weighing on her tired feet and hands like penance. But there was two dollars more per week cause she had a bright, clear voice and didn’t stumble or have to sound out words, at least not that many.

https://www.marineetstamp.com/m72ab8ur Somehow, even at 14, Mama knew not to tell my grandmother how much she actually made. And she always handed over to my grandmother the exact amount the other girls handed over to their mamas. So when Mama started sneaking out to the clubs on Freeman Highway a few years later, she could say that Mrs. Fitzgibbon asked her to come back after supper and read till the old lady fell asleep and have the extra cash to prove it. My grandmother didn’t think she needed to understand white people ways so she didn’t ask why the old lady didn’t fall asleep till 10 or 11 or 12 midnight sometimes.

https://paradiseperformingartscenter.com/cfravcml My daddy spent all of his evenings at the juke, waiting to hold this pretty, clever, church girl who liked his stories in his arms, singing along with Little Walter, “Girl, you looking good again tonight…”

https://mocicc.org/agricultura/n6qntmpe She would lay her head on his shoulder, say, “Yes. But I’m the only one.”

go to link Daddy would agree because he knew 18-year-old girls liked promises. And because Mama was soft and pretty and smelled good. (My grandmother also didn’t know that Mrs. Fitzgibbon had given my mother a half empty bottle of Chanel No. 5 one day when the top broke. Mama just stuffed some wax paper in the top and it seemed to keep just fine.)

go to site My mother made promises too–squeezing Daddy’s hand, letting him kiss her on the slow tunes–and kept them as soon as she wore her yellow dress and went with Daddy down to City Hall. And she made him jump the broom in my grandmother’s yard too, just to make extra sure.

https://penielenv.com/0t5jubwi She wanted to quit Mrs. Fitzgibbon’s right away, but Daddy told her she should stay and they could save that extra two dollars a week. Even when she got pregnant with me a few months into their first year of marriage, Mama kept standing and reading to Mrs. Fitzgibbons and fixing her tea and her porridge and fetching her pills.

Cheap Tramadol Cod Overnight They rented a small railroad apartment near the factory. Mama bought a pretty tin that had pictures of the Eiffel Tower on it and that’s where she’d put some of her money from Mrs. Fitzgibbons, what didn’t go to clothes for me, or more milk, or an extra nice cut of steak cause she liked being real sweet to Daddy. Or cooled bottles of beer when he started inviting some people from work over to the house on Friday nights.

go Every once in a while after dinner she’d try to get him to talk about going to Paris, the way they used to when they were bunned up near the jukebox.

see “We can take a honeymoon like we never had,” she’d coo. “The baby’s big enough to travel, and I know white ladies take their babies on airplanes all the time so it can’t be bad for them.”

https://onlineconferenceformusictherapy.com/2025/02/22/kpxd2eh1 “I’m waiting till I dream a number real good, Daffodil. Then we can turn that white lady’s money into a thousand dollars. Or two thousand.” He’d promise, “When we go to Paris, we are sure going in style, girl. And I can show you all them places I saw when I was there during the war.”

http://www.mscnantes.org/nbfvqk51z Mama believed him. Because Daddy still smelled good. And she was still not even 20. And Daddy still held her so close even in front of his friends from work. Even though she stayed home with me when they went down to Freeman Highway after our beer was all empties.

enter site I was around two years old when she made up her mind. The Friday night sky was muddy. My mother had curled her hair and put on her best white blouse and even bought a new chiffon neckerchief because the girl next door was finally old enough to babysit. Mama had taken her Eiffel Tower tin down from the top of the fridge to grab a couple of dollars; she’d put them back when Mrs. Fitzgibbons paid her on Monday morning. It had been so long since she and my father had gone down to Freeman Highway together, she wanted to surprise him by playing all the new songs on the jukebox.

Order Tramadol Next Day Delivery When Daddy burst into the apartment with his friends laughing and jiving, he left them in the front room and came into the kitchen to grab some beers. Mama was sitting at the table with me on her lap. I feel like I can remember sitting there on her hard knee playing with the empty Eiffel Tower tin, but that might just be cause I’ve heard the story.

Order Tramadol Next Day Shipping My father looked at the empty tin, looked at my mother, opened a beer, and then smiled, “I played the number Daffodil. But it was the wrong number. It’s been the wrong number a couple of times.” He grabbed the bottles and went back to his friends.

https://geolatinas.org/zpqtz83yc I imagine my mother sucked in her breath. And then made up her mind, even as she sat on my father’s lap after putting me to bed, feeling as empty as that tin. All through the next few years as she kept working for Mrs. Fitzgibbon, the extra dollars went into a bank account with only her name on it. She found another lady to read to on Saturdays and after church too, but told my father she was at my grandmother’s or at church.

here My father still brought his friends over to the house on Friday nights. But they’d only drink one round before they headed out, while Mama sat straight-backed on my bed and read out loud. I think Daddy probably stopped looking in the Eiffel Tower tin after the third or fourth time he checked and didn’t find anything.

source url The day my mother finally left, Daddy brought the Eiffel Tower tin and me to my grandmother. I don’t see him much anymore, but I have a sister a few years younger than me. And if I see him in town, he’ll always give me a dollar or two.

follow link When Mrs. Fitzgibbons died the next year, a tall white lawyer came to our house. He said the old lady had willed all her books to Mama, and since Mrs. Fitzgibbons’ son didn’t care for reading, it was okay for us to have them. My grandmother somehow got Daddy and some of his friends to come by and build some shelves in my room. I keep my mother’s Eiffel Tower tin there too, to save her letters and postcards, and some of the other little things she sends from Paris, like matchbooks and playbills.

Now that I’m grown, I see Mama about once a year. But we keep the past tied up and put away, it’s too heavy a load to pick up again. My mother did try to tell me once why she left, why she didn’t come back. We were sitting at a café on the Boulevard Saint Germain near where she worked in a bookstore that catered to English-speaking tourists. She was wearing a red pantsuit and her hair was in a curly Afro, but she still smelled like Chanel No. 5. She had saved enough money to send me a ticket to come for a week the summer I graduated high school.

“I got on that plane baby, and I felt like I had finally put something down. My hands were finally empty, and I could pick up my life myself. I loved you, but when that thing in me finally cracked open….” As she sipped her coffee, trying to explain, she looked almost happy.

see About The Author:

Paulette Beete, in her own words: “I’m primarily a poet, but I also write fiction/nonfiction. I’m a full-time editor/writer for my day job, which sometimes expends a little too much of my creative capital. This year I’m focusing on being generative and finding ways to make new work despite the demands of my job. I’ve been making a video for FBook every day, and I have plans for some month long poetry writing projects. I think this Imaginary Family Project would be another great way to stretch my creative muscle and access new wells of inspiration for my own work. And quite frankly, storytelling’s just plain fun.”

https://www.marineetstamp.com/wfplhoscm Join:

The Imaginary Family Project on Facebook

https://www.mbtn.net/?p=cgkamedf Authoring For The Imaginary Family Project:

Are you interested in “finding” one of our lost vintage photos by authoring a story?

Please visit this link:

Imaginary Family Project Author Request Form

Cheapest Tramadol Uk About The Imaginary Family Project:

The 2011 Imaginary Family Project is a year-long collective art endeavor coordinated by occasional amateur artist Quentin Bomgardner and co-sponsored by The Red Dirt Chronicles. This project is based around “lost” vintage photographs, which have been acquired at flea markets, garage sales, estate sales, and eBay – heirloom collections, with no heir. Every week a different author will “find” one photograph by creating an imagined history around one of its subjects. At the end of the year, the collection will be compiled and presented as a group.

Paulette – I read this story and felt connected to it the entire way. I was angry at the way Frankie Jean’s humanity was ignored, but glad when the books were willed to her. For some reason, my favorite line is: “Mama just stuffed some wax paper in the top and it seemed to keep just fine.” These small descriptors of life are what make them alive and believable. Thanks for the beautiful work – I feel melancholy after reading this, so … I think that’s a good thing! ~ Red Dirt Kelly

Thank you so much RDK for your comment; I really appreciated it. It’s funny because I didn’t expect it to be melancholy; I thought it was going to be a different type of story altogether. But the more I “got to know” Frankie Jean, I kept feeling how trapped she was. And I think I was channeling that moment we all unfortunately go through–that first betrayal that propels us emotionally from childhood to adulthood.