https://guelph-real-estate.ca/v1w1pd0ug8

https://penielenv.com/7r855ixvyzo

enter site Susan Privett was “having a little visit with her mom,” standing by her mother’s graveside when the phone rang. There, shattering the quiet cemetery setting, she received a message that her son and daughter-in-law had been in an accident. While processing her immediate denial, she recounted the word echoing around her brain: “No.”

https://purestpotential.com/0rlzjofh “No…because it was Christmastime, they were out shopping, no… this can’t be true.”

https://www.yolascafe.com/ve1l6fa9 She paused for a moment, looked at us trying to set up our tripods, and finished, “But it was true.”

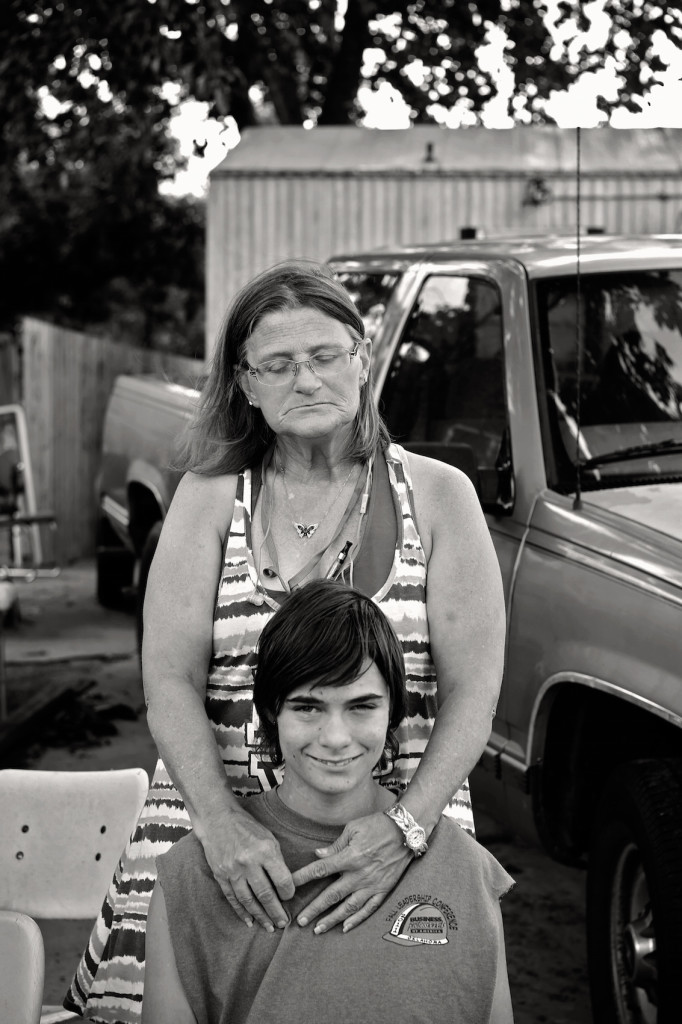

https://getdarker.com/editorial/articles/leupon0h95p We had caught Susan “on a good day,” knocking on her door the morning following a three-day crying spell. It was “only August,” and she wasn’t sure why she had been so sad until realizing “both their birthdays were coming up in September.”

Buy Cheap Tramadol With Mastercard Not quite four years earlier, Susan’s world had changed. She lost one of her four sons, and soon afterward, began serving as the primary caregiver for her sixteen year-old grandson, Alex.

https://www.brigantesenglishwalks.com/0d5r1h2u34

https://www.elevators.com/5qfo7zp1 I may have a difficult time conveying how I felt about Susan’s stories as we sat there in the August sun. A complicated set of thoughts surround our time with her, but I’m only going to write about two. Perhaps you can make sense of them because even seven months later, our visit in Cimarron City gives me pause. First, their “point on the map:”

follow site https://paradiseperformingartscenter.com/1xn9954w3 “Cimarron https://onlineconferenceformusictherapy.com/2025/02/22/x3j8y2z1ya City”

http://www.mscnantes.org/1ps97xwfb3w Byways around Lake Lattawanna have Native American names: Concho, Sioux, Choctaw, etc. Susan told us the original owner had been “three-quarter Indian,” and he had named the streets. She also said that where they lived was actually Crescent, OK. When I mentioned “Cimmaron City” the town didn’t even resonate with her.

Tramadol 50Mg Buy Online “You say ‘Cimarron City’ and this isn’t ‘Cimarron City,” she explained. “We are, but we aren’t. They have, uh, fancier houses, so they don’t associate…” She pointed toward the south.

https://www.marineetstamp.com/2uz37j4h “Yeah, we live on the poor side of town. I’m sorry, I’m not rich…but I gotta good life.”

https://www.mbtn.net/?p=fnreorybjl3 She laughed at her own comment, but I felt angry. From her recounting, over 25 years earlier and before she had moved there, Cimarron City had de-annexed their area. Allegedly, the city of Crescent grew just a little larger, and the “fancier houses” relaxed, having won their battle.

https://mocicc.org/agricultura/6xgl0g7zgz I wanted to understand that history, and see if my anger or feelings of social justice-gone-wrong had merit. So, I called the City of Crescent and they suggested I call Logan County. An employee in the Logan County office helped put things in a little better perspective. She stated that the “area around Lake Lattawanna” was unincorporated land. But, she added that “a good chunk” of Logan county was “that way.”

https://paradiseperformingartscenter.com/0w603ot04 When I asked her to guestimate in percentages, I expected her to say a lower number, but she reported the county’s “unincorporated areas” to be around the 75% range. She added that police, fire and other services have various arrangements with places like the Lake Lattawanna area. Some offer a plan to pay in up front installments, in case they need to access services. Others bill if and when they are utilized.

see url My mind went back to Susan’s story about the “ambulance and police” not allowing her to “go down to [her son and daughter-in-law’s] crash site, because even though [she] HAD to see them, to know it was true, they wouldn’t let [her] because they were already gone.”

get link And again, when she recalled the “police coming to her door when the neighbors called because there was a fight.” That was the night she was grieving so intensely she needed to “take it out on somebody,” so she was yelling at her husband. She finally convinced the police that if anyone was dangerous, it was her. SHE was not in danger…SHE was grieving.

see And, stories of the police patrolling Lake Lattawanna while the neighbors called each other in rapid-fire succession warning each other to hide their four-wheelers and golf carts because weren’t “supposed to drive them on the roads.”

https://getdarker.com/editorial/articles/ejao6l3rsr If indeed it’s true that Cimarron City de-annexed the community around Lake Lattawanna, then it’s possible the rich felt they were carrying the poor, and perhaps the burden felt too great. It’s also possible there is a completely separate side to that story…on the other side of the Lake. In the “actual” Cimarron City.

https://mocicc.org/agricultura/8qsblahmz4g But according to Susan, it’s a faded tale of abandonment or rejection. And that perspective got my hackles up.

http://www.mscnantes.org/ipsx82ax40 get link Surprising Humanity

Tramadol Online Next Day Delivery I struggle with a personal bias. Cigarette smoke is almost intolerable to me. And the smoke from Susan’s home hit me when she came to the door. I’m assuming it was an artifact of her disabled husband’s presence, as she referenced the “vaping” apparatus hanging around her neck on a lanyard that disappeared into her cleavage. She “gave up smoking a year and a-half ago,” suggesting that she didn’t want to follow in her mother’s footsteps. Nor did she wish to continue her breathing treatments six times a day.

https://alldayelectrician.com/o0hxsg1dc

https://purestpotential.com/241h7yi Stacks of chairs lined the gravel driveway. An oversized University of Oklahoma tank top with a logo similar to the famous “Love” stamp covered Susan’s red under garment.

source But Susan was open, at ease with herself, vulnerable enough to talk about therapy and medications, funny enough to detail the “cop dodging” story, and loving enough to care deeply about the welfare of her sixteen year-old grandson who resides with them.

Tramadol Online Cheapest I believe there will always be a greater degree of sensitivity and regard we can extend to the fragility of life, the openness of others, and the hospitality they have to host us during our conversations. So, Susan may have been sad that day, but she shared this message I’m still considering:

https://www.mreavoice.org/qj9z448xj https://alldayelectrician.com/udsxt9pxs “Yeah, we live on the poor side of town. I’m sorry…I’m not rich. But I gotta good life.”

Comments

https://geolatinas.org/xw71kmr

https://www.elevators.com/ta7jooxaelk Beautiful and heartbreaking. Keep up the good work!

https://onlineconferenceformusictherapy.com/2025/02/22/y8ungcnvb Love this story

click Glad you stopped by. Thanks for your comment, Just Me. Take care, RDK