https://www.brigantesenglishwalks.com/22sc33u

click https://www.elevators.com/8b9ozapx #47 of 52 : THE KALIN FAMILY via ELDRIDGE BENJAMIN

https://www.yolascafe.com/hwxo9vh9pzb Tramadol Online Overnight External Photo Clues:

None

see Order Tramadol Cod Online Imagine:

https://danivoiceovers.com/l4psg1ve The Skin I’m In

enter Well, she actually sent it. She sent it to my office. I’d never given them my home address. They’d never asked, not that I care. I don’t even understand why I’m even thinking about this. I was sure I’d put them behind me. But, looking at this picture of my ‘family’, I do feel something. I’ve considered waking Nzhinga. She’s great at this sort of thing. I’m not.

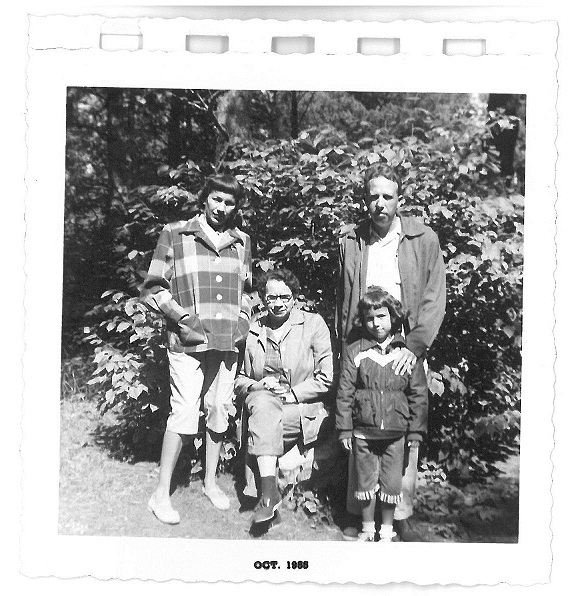

https://www.mbtn.net/?p=iu3nleue I’m looking at the photograph again. I examine the face of Edmund, my ‘brother’. At only 19, his drinking has clearly taken a toll on his body. Apparently, he’s close to his niece, Mildred’s daughter. I almost feel programmed not to look at Mildred. My mother often explained that it was loathsome enough to be ugly on the outside, and the very least I could do was to avoid ugly thoughts. I regard my mother’s countenance. Even though I’m thousands of miles away, I can’t help but to feel like she’s judging me. Her scowl suggests that, as I stand in her judgment, the verdict is unfavorable. It’s as though her disapproval has, somehow traversed the sea, implanting itself into my life.

https://lpgventures.com/sdpfe7ovrnw Perhaps, I’ll always be the ingrate who’s never shown gratitude for a mother who provided the best education that money could buy. She’d sent me plane fare for me to return home for Mr. Kalin’s funeral services. I was unmoved by her attempt to display me as a walking, talking example of Mr. Kalin’s benevolence. On the other side of the planet, I now meet total strangers who have validated me in ways that Annette Tennyson never cared to. It’s difficult to look at her without being reminded of so many things. I can’t help but to wonder how my father would feel, looking at this family photograph. I hope he’d agree that a family photograph without Ernest “E.B.” Benjamin, was hardly worth sending.

https://paradiseperformingartscenter.com/c5k38ke The last time I heard my father’s voice, the smooth tenor was distorted in pain, anger, and shame. Even if it hadn’t been the last time I’d see him, the memory would have still stuck with me. His hurt was so raw. At the time, I was only seven years old. Most of what I overheard, didn’t make sense. Mr. Kalin had shown up in the garage to speak to my father. That had never happened before. My father usually received his instructions from Mrs. Kalin.

click here Mrs. Kalin had passed on. The doctor would be moving to Queens, as the house in Williston Park belonged to his wife’s family. Mr. Kalin was clear. He’d have no further need for a mechanic or a driver. I remember wondering how he’d get to his office. I’d heard my mother say that he was an important man at Silvercup Studios. It struck me as odd because Mr. Kalin was old, not young and strong like the men who were in the motion pictures.

https://guelph-real-estate.ca/74o8faymr My father made friends with just about everyone he met. He once, through an Italian janitor at the studio building, arranged for me to watch an afternoon of movies with the janitor’s son. Dad fixed the guy’s car in exchange for the favor. But Florio would’ve been satisfied with my father’s stories about Mrs. Kalin. It was a great afternoon, but I remember being more entertained by my father, than I was by the movie. I felt an unfamiliar ambivalence about the films. While the characters on screen were beautiful and rich, and my mother valued those attributes above all else, I was watching a world that I couldn’t touch. I was much more comfortable laughing with my father, who always welcomed a hug, and never worried about his clothes being wrinkled. I’d never felt loved by the beautiful, or the rich. My mother was less than subtle about her disappointment that I’d inherited the complexion of my father’s Ibo grandmother. In her eyes, my dark skin was an obstacle that stood between her and the social status to which she aspired. And I don’t recall a single day with her when she didn’t take the time to let me know that.

source site My father never spoke about skin color, directly. He would simply re-tell the story of the Parable of the Talents. He loved the story, because there were no ‘bad guys’. There were just people who were doing what they thought was best, with what they’d been given. However, the son that was best equipped to make the best use of what he’d been given, was the most intelligent. My dad saw himself in the story. He understood his life as a simple one. Although he hadn’t completed high school, he understood his own talent, his own gift. He was blessed with an intellect that made it possible to master anything mechanical. Even as a child, he’d tell me, he was amazed by machines. He’d spend hours examining the intricate gears and pulleys, trying to understand how they functioned. He told me stories about Benjamin Banneker, a Black man who’d built a clock, and went on to become an architect, designing many of the government buildings in the nation’s capital.

https://purestpotential.com/463jvrjn6e Dad had little use for the life that my mother wanted for herself. Though he never discredited the importance of education, he held fast to his own interpretation of the teachings of Dr. Booker T. Washington. Dad felt that Black people in America should become educated, in order to develop the skills necessary to build their own institutions and communities. It was only then that they’d be respected by other peoples of the world. That was the reason why, although he read incessantly, he’d vowed never to sit in any classroom and subject himself to what Dr. Carter G. Woodson described in The Miseducation of the Negro. My father had nothing but disdain for Black people who were college educated but, somehow, unable to establish their own businesses. He often said, ” A servant, who chooses to be a servant, is way worse than a servant with no choice.” He saw himself as a master at his vocation who, if anything, should be teaching. And, while his occupation lacked the status that my mother wanted in a husband, he was sought out by anyone who knew him, as a knowledgeable source when it came to automobiles. He’d worked for Mr. Kalin for three years before he met my mother at Silvercup.

https://purestpotential.com/1kf4n9udn My mother came to New York from Virginia, which she didn’t consider to be part of the South where the ‘ignorant coloreds’ came from. She moved to New York and got work as a housekeeper. She worked and lived with a wealthy family in Brooklyn who, according to Annette, recognized her ‘good breeding’. When she had time, she tried to position herself to be ‘discovered’ by someone in search of an actress. Although she had no accomplishments to her name, Annette Tennyson was proud. She’d never lower herself to visibly pursue anything, no matter how badly she desired a given thing. She was to be pursued, not the other way around. She’d been raised to hold herself above other people of color, by virtue of having a white father. My grandfather, Jonas Clifton, made sure that his seed would be the only thing that he’d ever give to Althea Tennyson. Despite the fact that her conception was less than consensual; my mother was worshipped as a gift, which marked the beginnings of progress and change for the humble, but proud family. They often bragged that, in a new city, she probably wouldn’t be recognized as colored. When Annette decided to leave home, her family was confident that it wouldn’t be long before she’d be moving them all to her New York City home.

https://penielenv.com/p0to8gsq8 Though my mother worked in Brooklyn, she traveled to Queens when she could. After all, studio executives wouldn’t be coming to Brooklyn, looking for her. My father spoke to her for two weeks, before he got up the courage to offer her a ride. Of course, had my mother realized that he was a driver, she’d have never accepted. She assumed that the brown-skinned man who joked, casually with studio staff had to have been an actor. He was charming and, for a colored man, rather handsome. Surely, he’d been cast as a butler or cook, of some sort. And E.B. was a natural storyteller. However, the quality that seemed to draw people to him was his genuine interest in listening to the dreams and passions of other people. A staunch advocate for the pursuit of happiness, he encouraged Annette to open herself up to success as an actress. He described Mr. Kalin as a fair man who might consider hiring a colored woman, if the right one came along. More conniving than talented, Annette soon got E.B. to introduce her to Mr. Kalin. At the same time, Mr. Kalin was an employer, not a friend. E.B. knew that the matter had to be handled delicately. When Mr. Kalin’s housekeeper took ill, he asked E.B. if he knew anyone who could fill in. Annette had her opportunity.

get link Mr. Kalin saw Annette as experienced, intelligent and, for a colored woman, quite attractive. Mr. Kalin hired Annette to fill in for his ill housekeeper. Meanwhile, he arranged for E.B. to drive her to and from work. Their relationship developed, I was conceived, they got married and moved in together; not, necessarily, in that order. There are those, however, who insist that my mother’s relationship with Mr. Kalin was closer than her position would imply. So, Mrs. Kalin’s illness would prove to be Annette’s second great opportunity. Mr. Kalin announced that the needs of his wife and kids would be better served by a housekeeper that resided in his home. When Mrs. Kalin was moved to the hospital, and Annette’s family continued to reside in the home, it was suggested that there may have been some truth to the rumors.

go to link Such seemed to be the case when my father was visited at the garage, by Mr. Kalin. Dad often asked about Mrs. Kalin’s condition. He understood her as a good woman, at heart, and prayed for her speedy recovery. Unfortunately, his intentions were not enough. Mrs. Kalin had expired on the morning of October 12, 1940. My father was told that, while Mr. Kalin would no longer require the services of a driver and mechanic, he would still need Annette’s help with his children. Mr. Kalin claimed to appreciate my father’s understanding. In addition to Annette’s room, board, and salary, he’d provide for my education. Although he would clearly have use for a housekeeper, having a Negro mechanic on his property would complicate the adjustment to his new community. When E.B. was finally clear about what it was that Mr. Kalin was struggling to say, he felt both angry and powerless.

go He was from a proud family. He’d been raised by men who’d always made their own way. Still, as the nation was approaching war, it was clear that times were changing. It was said that, after the war, there would be many opportunities for people of color. He was intrigued by the possibility of another life for his son, a life where he could possess education and status, as well as dignity and independence. He could make his son into a master mechanic. But he knew that his son wasn’t passionate about machines, at least not in the way that he’d been. Winston was a part of a new generation, with new ideas, and new possibilities. Mr. Kalin was offering access to a life, where his son would never have to face separation from his family. E.B. couldn’t offer his family much but, perhaps, he could allow this opportunity to be given to his son. He thought he might decline the offer, and move his family back to the south. However, the thought didn’t live long, in his mind. He knew Annette. And Annette was likely to hop into the shiniest car leaving the Kalin home. And that car belonged to Mr. Kalin. Dad would be leaving the Kalin home, and his family, on foot.

https://www.mbtn.net/?p=yvkvvvav Before leaving, my father said to me, “I want you to promise me that you’ll get far enough away from these small-minded folks, far enough away that you’ll be able to find your own path. And I know that your path will, at some point, meet up with mine again. I’ll see you then, son.” And with that, he left. I later found out that he’d enlisted in the military, to support the war effort. Initially an auto-mechanic, he proved to possess the aptitude that would make him a valuable asset as an aircraft mechanic. My mother always explained that she remarried after my father was killed in World War II. Technically, that could be considered true. It is, however, a lie by omission.

follow link When I was eleven years old, my path crossed with that of Lt. Col. Bradley Biggs. Like my father, the man I came to know as ‘Uncle Biggs’ agreed that life in the military offered few opportunities for Black men. Still, as civilian life offered even fewer prospects, both men decided that their job would be in support of the war. On April 5, 1944, I received the first letter from Uncle Biggs. The letter included an article from the military post newspaper, about the March 4th 1944 ceremony, “First Negro Chute Officers Given Wings”. More importantly, Biggs wrote to tell me that my father had been killed in an accident with an aircraft engine. The March ceremony was bittersweet for Biggs, for whom my father was an important ally. To Biggs, my father was an honorary member of America’s first all-Black paratroop unit, known as The Triple Nickels. He and my father became friends mainly because, unlike many of his fellow Black officers, Biggs was not college-educated. Besides, being from Newark, he and my father could relate to one another. Biggs wrote to me to offer his condolences and, more importantly, to send me my father’s dog tags. According to this officer, my father looked forward to introducing me to my ‘Uncle Biggs.’ Biggs and I stayed in touch. I stayed in school, motivated by his stories about the changing world.

go to link Biggs shared my father’s world view. The fact that they both saw themselves as equal to, or better than, any other man, led to many long talks about the duty of the Black man. They both felt that the future held great promise and, according to Biggs, my father was certain that I’d be part of shaping a new vision for the children of Africa. The lieutenant thought that it was important that I understood the vision that my father had for me. My father, despite his intelligence, was a poor writer. That, Biggs would later tell me, is the reason why he never wrote me. Being a proud man, he was always self-conscious about the way that he was perceived, and would never allow anyone to see anything other than his strengths. Besides, he was certain that the letter would be intercepted, and ridiculed, by my mother.

https://guelph-real-estate.ca/oxkiscgcn5t Biggs often commented on how well I described the events at home and school, in my letters. And, although he often asked, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. I was about to be sent to high school in another country. In my adolescent mind, that was enough to think about. By 1944, the Catholic Missions of Nigeria were unanimous in their desire to establish a fully accredited University in West Africa. They considered Nigeria an ideal place for it, and Annette considered the Catholics to be the sole authority on everything. This was her third great opportunity. She explained that I’d be more ‘comfortable’ amongst people who looked like me. Besides, she was uncertain that I’d be able to compete with the white students at American schools.

source site Biggs didn’t know much about Nigeria, but he shared what he did know. What he knew was that this is a big planet, filled with interesting ideas, people, and places. The world is filled with truths that don’t always make their way into the curriculum of the American public education system. Biggs was certain, however, that an exciting and fulfilling life could be had by any child of Africa willing to trust their own ingenuity. He looked forward to hearing about my study in Nigeria. He claimed that it was a pivotal time for the independence struggle of African peoples. I came to understand that he was right. However, that didn’t even occur to me until I became accustomed to the way in which I was embraced by the African students. They accepted me as a part of their lives in ways in which my own mother had failed to accept me. You see, during my freshman year, Annette became Annette Kalin.

https://paradiseperformingartscenter.com/hiozqyj I rarely had time, however, to think about my mother’s disloyalty. In West Africa, I was a man. I was afforded the respect of a man. I would learn that, with that respect, came the duties and obligations that were thrust upon African men, charged with the responsibility of gaining independence for their people. I was scared by the possibility of failure and, more than once, abandoned the cause. Unlike my schoolmates, I could always finish school and work as a mechanic with my new stepbrother. The problem was that Edmund, who isn’t even the best mechanic in his own household, would have been my new boss. His incompetence is, in part, due to his alcoholism. Still, one cannot underestimate the role that his stupidity has played in all of this. At any rate, I was certain that the business would fail, and I’d be blamed. Besides, Nzhinga refused to go to the United States. “My struggle is here. I thought you understood that. From what you’ve described to me, your return to the home of your mother, would mark the acknowledgement that this world is too much for you to face. If that is true, I should be glad. I have almost made the mistake of falling in love with a coward.” I decided not to run home.

https://www.mreavoice.org/gw5gcm3qbyv I’d never considered myself a cowardly man. I understood the importance of Kwame Nkrumah’s demand for “Self-Government Now.” But our honorable principles were little defense against what we faced in January of 1950. I worked as a writer, for the Convention Peoples Party (CPP). Our press was shut down, as we were charged with sedition. Every couple of weeks, a different CPP leader was charged with some offense against the ruling government. Nkrumah was fined for contempt of court.

https://www.elevators.com/3h62q1igk3 The tension, created by our “Positive Action” campaign, continued to escalate until the Governor declared martial law. For two months, the authorities deputized Europeans to terrorize us with handguns and clubs. They brutalized and beat many of us, without cause. Many of my friends were shot. My office at the CPP press was raided and our files and property was taken. Most of our party leaders were taken into custody. In doing all of this, they sought to destroy the spirit of our struggle. Our political victories during the April 1950 elections proved that they were unsuccessful. The British Governor was forced to release Nkrumah from jail and recognize him as the head of the majority party delegation in the Assembly. In 1954, Pres. Churchill officially recognized Kwame Nkrumah as the Prime Minister.

enter Our movement was significant in that, for the first time in a long time, we were self-defining. We no longer needed European or American recognition, in order for us to claim our nationhood. Mr. Nkrumah appointed me to head the Department of General Studies at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Not long after, I asked Nzhinga to marry me. It was difficult to get her to accept my proposal, without meeting my mother. She helped me to understand the deep and complex love that I had for my mother. I learned, from her, to accept the mother I had. I learned that for me to expect her to be other than herself, was no different than her failure to accept me for who I was. Nzhinga taught me that my mother was a victim of the same institutions from which we sought to free our people. She helped me to understand that, though we are endowed with a divine freedom, men have conspired to enslave the minds of the people. It is our job to bring peace to the world. I am often reminded of The Parable of the Talents. I resolved to embrace the gifts with which I’d been blessed. Over time, the feelings of inadequacy, the perception that I wasn’t good enough, slowly left my mind. Once I got rid of my fear, I was able to trust that I’d be able to master whatever situation I faced. Once I embraced trust, I was able to relax, let go of control, and live my life as the adventure that it is. And, once I relaxed, my truer self was able to emerge. That true self, is a writer. More importantly, I am a writer who wants to lead others to the freedom that I’ve discovered within myself.

click here I assured Nzhinga that I’d introduce her to the other individual who helped navigate me through the contradictions of Black life. With that in mind, I used the money that Annette sent me. I flew, with Nzhinga, to Fayetteville, North Carolina. I took her to meet Uncle Biggs.

Tramadol Cheapest Looking at this picture tonight, I can admit that my mother taught me a lot. I understand that a man can waste a lot of time and energy, in a struggle to be accepted by those who don’t want him. We all have the power to create the life that we want. And those who stand in opposition to us can neither help, nor hinder us. As we choose freedom, we choose to accept that we are brilliant.

https://alldayelectrician.com/98xesh6 https://mocicc.org/agricultura/nhzvn1oa7zs About The Author:

Seanz Brother is a born-again writer. As you read this, he is vanquishing from his mind, the last vestiges of doubt that one can ecape the mundane existance of believing that it’s implausible for a man to provide for his family, by pursuing his passion. He’s been recently paroled from the prison of fear that attempted to shackle a blue-collar on him, while he prefers not to be bound to any collar. Perhaps we should monitor him closely…These newly liberated ones are easily seduced back into The Matrix.

https://lpgventures.com/xt9rps9p9 https://www.mreavoice.org/vp2ybbahv91 Join:

The Imaginary Family Project on Facebook

https://onlineconferenceformusictherapy.com/2025/02/22/kkx3ty8n http://www.mscnantes.org/r9wjz17 About The Imaginary Family Project:

The 2011 Imaginary Family Project is a year-long collective art endeavor coordinated by occasional amateur artist Quentin Bomgardner and co-sponsored by The Red Dirt Chronicles. This project is based around “lost” vintage photographs, which have been acquired at flea markets, garage sales, estate sales, and eBay – heirloom collections, with no heir. Every week a different author will “find” one photograph by creating an imagined history around one of its subjects. At the end of the year, the collection will be compiled and presented as a group.

I really enjoyed the story. I like the father who disdains any black other educated. He is quite correct