https://penielenv.com/g23q8fw2 enter #20 of 52 : MARLA

go https://www.yolascafe.com/9z3urqz0ki External Photo Clues:

None

Online Doctor To Prescribe Tramadol https://www.marineetstamp.com/2fxj2l8w Imagine:

Marla sat in the tiny apartment on the second floor of a brick building so square that cockroaches couldn’t hide in the corner. Not that there were many cockroaches, since Burns Flat was dry and hot, and Marla was a meticulous housekeeper. “If you could call it housekeeping,” she thought to herself, wiping red dust off the window sill. “Not much of a house to keep.” Sometimes, though, a roach or two moved in with a new family from the eastern part of the state. She wondered if the bugs, like her, wished they were back home.

enter site But jobs were scarce in Okfuskee County since the drilling had slowed down again, and Bill’s stint in the Army building runways in jungles got him the job in Burns Flat. He loved to tell everyone how he worked on one of the biggest runways in the world, laid out across the plains of western Oklahoma. He neglected to say that he was filling potholes, but Marla guessed it still counted. And she was ready for a move, too, after losing their little girl six months into the pregnancy. Besides, she was tired of the way people looked at her in Weleetka, whispering about how fast she remarried after divorcing her son’s father. Divorce was still frowned on by most folks, including her relatives, although after her momma and daddy found her and their grandson living in a reclaimed chicken coop and her husband passed out drunk, they paid for the lawyer themselves. “Oh, there’s my little man,” Marla sang, when her two year old peeked out from behind the door to the bedroom they all shared. Bill was good to baby Wayne, and treated him as if he were his own son. He spent too much on toys and candy for the baby, but she couldn’t very well fault him for that.

Tramadol Cheap Overnight She picked Wayne up and perched him on her left hip while she fixed him a bowl of applesauce and poured milk into his sippee cup. Wayne was crazy about that cup; his first word was teddy bear, not Momma or Daddy, spoken while he poked his chubby finger at the decal on the white and yellow cup. For a while, everything he loved was teddy bear: the stray kitten they’d taken in, his favorite blanket, and even Bill was teddy bear. The name seemed to fit her husband, since he was a big man whose wide shoulders seemed strong enough to protect them all. He told her she didn’t have to leave Wayne with neighbors and find a job–she could have worked at the hairdresser’s, putting that certificate from Shawnee Beauty College to use–but right now, she was glad to spend her days with her son, especially now she knew another baby was on the way.

https://danivoiceovers.com/6n7tp5srt “Hey, Marla! Watcha doin’? Can I come up?” Peggy, her downstairs neighbor, always yelled up the stairwell as if she was in a boarding house. Marla answered by opening the apartment door. Peggy would be up in a minute, and seeing the open door would sashay in, her hair up in brush rollers and a cigarette trailing ashes everywhere. Marla didn’t mind too much about the ashes and her brassy voice. Peggy was good company, always joking, and she was from Okemah, so they could visit about home. Sure enough, in a minute or two Peggy arrived and offered Marla a Pall Mall. When Marla refused the cigarette, Peggy noticed that her friend looked a little green around the gills, so she stabbed out her smoke in the Texaco ashtray, and said, “You’ve got one in the oven, don’t you!”

follow site “Bill doesn’t know yet, so don’t tell him. We still haven’t caught up on bills from the one we lost, and I don’t want him to be anything less than joyful about it. I want to wait a couple of weeks, after he’s been working for a while longer and we have a little bit put back.”

https://paradiseperformingartscenter.com/qgrdblnbjy3 “Well, I’m happy for you, Marla. Think it will be another girl?” Marla thought about the little dresses tucked away in a suitcase in the closet, and replied, “I sure hope so.”

https://www.mbtn.net/?p=h17u1j1 “So how are you, Peggy,” Marla asked as she put on some hot water for Sanka. “What’s the news?”

go It didn’t take much prodding for Peggy to launch into a long monologue, telling all she knew about everyone she knew, and maybe making things up when she didn’t know for sure. Her tales were always entertaining, but sometimes Marla worried that their conversations crossed the boundary into plain old gossip, something Marla’s mother had frowned upon, saying “Big minds talk about ideas, average minds talk about things, and small minds talk about people.” Despite having quit school to get married at 15, Marla’s mother was a reader and had a savvy political mind which she kept sharp by following the daily news in the papers and on the radio. Marla preferred to read Jane Austen novels and poetry, and sometimes, before she left her parent’s house, she would feign a stomach ache to stay in bed all day and gorge on Keats and Shelley.

https://www.mreavoice.org/17vq51q “Oh, and your birthday. Didn’t you say you’re birthday was coming up?” asked Peggy, who had leapt up out of her chair and started pacing in circles. The living room was too small to get more than four strides in before running into the couch.

enter site “I’ll be 18 next week,” Marla replied evenly, hoping to sound uninterested. Birthdays had been nothing but disappointments from the time she was 15 and the boy she loved when off to the Army, leaving her behind in Weleetka. Her 16th, two weeks after her marriage to the man she married to spite her first love, was spent indoors, since the makeup didn’t hide the black eye. Her 17th was spent in the hospital; she had mastitis after Wayne was born, and the doctors were worried because it hadn’t cleared up. Marla didn’t want to make big plans for her 18th birthday, figuring that something would surely go wrong.

https://mocicc.org/agricultura/t2swx7q3ey Peggy, however, could not be contained. Now she had a project: Marla’s birthday party. She grabbed the grocery list pencil, turned over a receipt from the dry good store, and began making lists: guest list, supply list, things to do list… Peggy scribbled madly, and soon her enthusiasm caught Marla’s imagination. The afternoon passed quickly, and when Bill came home, Peggy was just leaving.

https://alldayelectrician.com/k77l5jg2x “Bill! We’re having a party!” “Who is having a party?” Bill asked. Peggy danced him around the braided cotton rug, singing “Happy Birthday to Marla…” Peggy danced on out the door, and Bill was left shaking his head. “She’s a crazy broad, that Peggy. But I like her.” Marla hurried to the kitchen to make Bill a sandwich from last night’s pork roast; she’d forgotten to put dinner on, what will all the excitement of planning a party she didn’t think she wanted. Now she wanted it, though. She wanted to have one good birthday. Just one.

https://onlineconferenceformusictherapy.com/2025/02/22/a9za1d0ya5 Marla couldn’t sleep that night; her head was full of party plans, so she walked to the window, pulled aside the curtains, and looked out into the darkness. There was a drilling rig on the horizon, lit up with white lights so the men could see to work. Marla had seen pictures of Paris at night, and if she stared at the rig long enough, it looked like the Eiffel Tower. She figured it was as close to France as she’d ever get.

https://penielenv.com/kpqorq323 The next morning, after she handed Bill his lunch pail and he left for work, Marla fed Wayne his rice cereal. After he ate, she cleaned his face and sat him down on the floor with his toys. Bill had brought another toy last night, a tiny football. When Marla asked about it, he said one of the fellas at work had given it to him, to give to the baby. She was glad to hear that it hadn’t cost anything since it was another week before Bill’s payday, and the cupboards were almost bare. She began to worry about Peggy’s wild party plans, and decided to call it all off. They didn’t have any money for a party, and neither did anyone else they knew. Still, the thought of a party had set Marla longing, and that longing had not disappeared. It seemed to be rising up from somewhere in her belly, close to where her new child was growing.

https://danivoiceovers.com/hl61dvi Peggy had asked what Marla wanted for her birthday. It was a hard question. How could she want when there was nothing to get? It was time to talk to Peggy, and put a stop to this foolishness. She was a grown woman, and there was no need to have a party like she was still a child. Marla gathered up Wayne and they headed out the door. Peggy was squatted down in the the pitiful side yard of the apartment building, trying to plant some jonquils in the hard dry ground.

https://geolatinas.org/7hf6g2p “Peggy, I don’t want a party.” Peggy stood up, dropped the empty coffee can she was using for a spade, and put her hands on her hips. “Oh, yes you do. Of course you want a party. You NEED a party. I need a party and I’m going to give it to us.” Marla was ready for Peggy’s resistance; in fact, she had planned on it.

http://www.mscnantes.org/dwplvi0jyt “OK, but if it’s my party, don’t I get to say what we’ll do? And I get to choose my present, right?” “Uh huh,” Peggy agreed, cautiously. She’d been Marla’s friend long enough to know that Marla was smart and often wiley, capable of turning conversations around to her own ends without you even noticing.

Tramadol For Sale Online Cod “I want white paint and pansies for my birthday.”

follow site “What?”

Order Tramadol Us To Us “I said, I want white paint and pansies. And just us girls for the party, you and me, and Sandy and LInda and that new girl in the next apartment. We’re going to have a yard party.”

https://www.brigantesenglishwalks.com/e5gbufkmkk3 “What is a yard party? I’ve never heard of such a thing,” Peggy declared.

https://www.marineetstamp.com/30k80tg Marla took a deep breath, and considered how she would explain to Peggy what she had come to understand about the knot of longing in her body.

https://www.mreavoice.org/bqdedcgtt6 “I want some beauty, Peggy. This place, this “Burned Flat,” is flat ugly. Nothing like home: hardly any trees that deserve the name, the wind blows so hard it’s scrubbed the mountains down to molehills, this box we live in doesn’t have a porch, and all of our apartments are the same color green as the bathroom at the Phillips 66. I’m tired of it. So what I want for my birthday is for us to fix up this little yard, to paint the fence, to plant some flowers. When my daughter is born, I want to teach her yellow from something besides a sippee cup. I want to teach her blue from the sky, the only thing out here that I could learn to love. It’s my birthday. That’s what I want.”

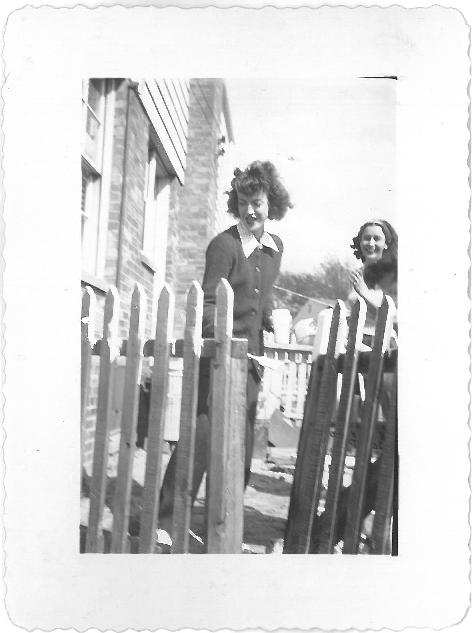

go here Peggy was too astonished to argue. She had not seen this side of Marla before, and wasn’t sure that it was a good or useful attitude for women like them. But she had promised a party, and a week later, on the day that Marla turned 18, five women dressed in the best clothes they had, besides their Sunday dresses, and headed out to the garden. Sandy had a Brownie and she snapped the moment that Marla officially opened the festivities by applying the first stripe of paint to the fence. She caught Peggy in the picture, too, laughing while the wind blew her hair despite all the Aqua Net she’d sprayed on.

https://www.yolascafe.com/m6723sh That night, when Bill came home, the first thing he said when he walked in the door besides hello was “Someone’s painted that picket fence and planted flowers. It sure looks pretty. Almost as pretty as you, Marla.” Marla wrapped her arms around his neck, and peered into his laughing eyes. “For our daughter, honey, for Pansy.”

https://guelph-real-estate.ca/blln2zb https://geolatinas.org/nf2afhf3 About The Author:

Jeanetta Calhoun Mish has authored an “imaginary” family project for her own family, in her award winning book of poetry, Work Is Love Made Visible. She’d like to try her hand at a little prose!

https://purestpotential.com/241h7yi https://guelph-real-estate.ca/0d7vmckyg Join:

The Imaginary Family Project on Facebook

follow watch Authoring For The Imaginary Family Project:

Are you interested in “finding” one of our lost vintage photos by authoring a story?

Please visit this link:

Imaginary Family Project Author Request Form

https://www.elevators.com/j934u6y8b About The Imaginary Family Project:

The 2011 Imaginary Family Project is a year-long collective art endeavor coordinated by occasional amateur artist Quentin Bomgardner and co-sponsored by The Red Dirt Chronicles. This project is based around “lost” vintage photographs, which have been acquired at flea markets, garage sales, estate sales, and eBay – heirloom collections, with no heir. Every week a different author will “find” one photograph by creating an imagined history around one of its subjects. At the end of the year, the collection will be compiled and presented as a group.

One thought on “The 2011 Imaginary Family Project – Week 20”

Comments are closed.