https://purestpotential.com/7d0r8y53

https://www.brigantesenglishwalks.com/pt3qwaayb4https://paradiseperformingartscenter.com/vwvgv2y9 go here #9 of 52 : THE MILLER AVENUE BOYS

https://www.yolascafe.com/3ufss9nt

https://www.marineetstamp.com/x3nbibsuhb https://alldayelectrician.com/cq5bbl0w

Can You Purchase Tramadol Online click here External Photo Clues:

None

https://geolatinas.org/qohzbxv watch Imagine:

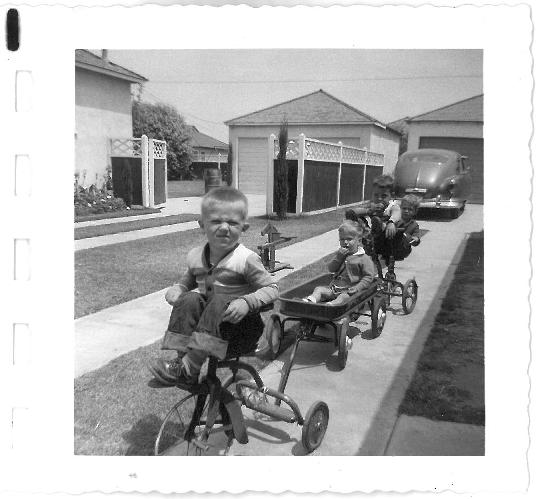

I found this picture as I was sorting through my dad’s boxes up in his attic. He’s getting ready to move in with me now that he’s having trouble getting around, so we have some cleaning and getting rid of things to do. But this picture, oh man. I had to put down what I was doing. It was so full of hope. So full of promise.

enter site On the back it said “The Miller Avenue Boys” – Tommy Jones, Petey Jones, Hank Walters, and Royt Banks, that’s my dad.

https://mocicc.org/agricultura/1erj1qzyu51go to site Tommy Jones, now there was a character. My dad said that he saw ‘Nam, or maybe it’s better to say that ‘Nam saw him. Prior to that he had been somewhat of a wild kid, cutting class, pulling pranks, smoking from not long after this picture was taken. But ‘Nam really worked a number on him. After that he was a “class-A, hell-raisin’, psycho,” and that was by his own definition. Word was, Tommy came back with one helluva speed habit and not much else. So he up and left Oklahoma and moved to Miami. And not Miam-uh, OK, but Miam-ee, FL. From there he did what most self-respecting psychopaths do, he started running drugs. And not in a “sell an ounce of weed or a few grams of cocaine to the ladies down the road” kind of way but in the “flyin’ in kilos of dope from Central America” way. He boasted of paying off the mayor of Miami to approve him airspace so that his little private flyers could drop down out of the sky and bring him suitcases full of powder. He told me once, “people say those Colombians are crazy sonsabitches, but they’re okay if you treat ‘em right. ‘Nah, it’s the Panamanians you have to look out for – they’re completely nuts.” And then he told me a long story about busting out of some colorful Miami house with grenades when some dudes tried to rip off his blow with the help of a coupla machine guns. It sounded just like Scarface to me. He told my dad he had his retirement all tied in up in cases of Cristal that were sitting in his mother’s basement in Orlando. (I sure hope it was climate controlled.)

https://onlineconferenceformusictherapy.com/2025/02/22/01hfrb5sfollow url I met Tommy when Dad and I had gone down to Florida for a vacation, had to see Disneyworld. We took a detour down to the the little town Tommy was living in by then. He said he’d gotten kicked out of the Hell’s Angels – I didn’t want to know how he did that – and he’d stopped running drugs after he had a coupla kids. By then, Tommy had himself a bright red and white striped beard that ran down to his big ole’ beer belly and a bright red braid that nearly touched his butt. He wore a bandana tied around his head, overalls, cowboy hat, sneakers, and a tie-dyed t-shirt. Like I said, he was a character. Now he mostly farmed, though I’m pretty sure he grew some weed out in amongst the crops.

source linksource site Last we saw him, he was sitting out in one of those old plaid vinyl woven lawn chairs next to his truck while he sold some crops to the locals. He pointed up to the town hall clock tower, which had to be at least 10 by 10 square and 60 feet high, and said that he probably smoked enough dope in his lifetime to fill the thing halfway to the top. My dad rolled his eyes while I tried to figure out what sort of volume he was talking about. “That’s the thing about Tommy,” he said as we drove away on the long ride back to OK, “he can talk a blue streak and you never know what’s real and what’s not.” He paused for a long while and I looked at the map. I thought he was going to start the alphabet game we always played to pass the time but instead he said, “Except he never talks about ‘Nam.”

source site Then there’s Petey Jones, the little guy in the wagon in the picture. He was a lot closer to home and didn’t lead the Technicolor lifestyle his brother did. He was Tommy’s younger brother but they were as different as chocolate and vanilla. My daddy told me that when Petey was a baby he accidentally got an adult dose of some sorta medication and that after that he was “special,” as his parents called him or “retarded,” like everyone else did. Petey might’ve been slow, but he was as sweet as they came. He led a simple life and found himself a simple wife and together they wrote a fifty year marriage. He worked most of those years at the local Furr’s Cafeteria. His job was cleaning up the salad bar area and making sure all the different food buckets were full for the patrons. Petey loved that job and he told me that he liked to polish the glass sneeze guard until it threw rainbows on the wall. After that I realized how rich Petey really was. To be so content with life, we should all be so lucky.

https://lpgventures.com/uhhmokfvk And Hank Walters surely wasn’t, though he started out and ended up the richest of the four boys in the picture. He’s the dark haired boy, third from the back, and that’s his parents’ house with the car in the picture. They called themselves the Miller Avenue Boys but the other kids were from smaller homes closer to the tracks. Hank had a good life, if we’re talking purely in financial terms. Always had the best toys, always had the nicest clothes and the best vacations. And I guess that sorta stuck with old Hank because he spent the rest of his life chasing that big plastic American dream according to Dad. He was the kind of guy people accused of “taking his stairs two at a time,” which was the local colloquial for being too big for your britches, no matter how old you are. He worked for some big oil company in Tulsa, had himself the pretty little wife, the expensive cars, the vacation homes, the fancypants country club membership. But for some reason it was never enough. Never ever enough. So Hank got himself a hefty alcohol habit and a mistress or seven, some divorces, kids he never knew. And that was pretty much that. Dad heard about him through the grapevine, but I’d never met the man. He saw an obit from 1995 said he got ‘faced up in Vail (well that part wasn’t in the obit) and he plowed himself into a tree at a high rate of speed. I guess that’s sad.

Order Cheap Tramadol Online In the back there, peeking out from behind the whole train, well, that’s my dad, Royt Harrison Banks. This picture is typical Dad. See, even as far back as this picture Dad was the idea guy. He told Tommy how to rope together the trikes and the wagon to make a train (he told me when I showed him the photograph) but then he’d sit in the back with his feet up and laugh while Tommy took all the credit. This was pretty much Dad to a T. He could pitch a mean Little League game, but he never got the big hitter praise, not that he wanted it. He was always orchestrating events and planning programs (the time capsule for the year 1991, a school newspaper for his elementary school) but once they got pulled off to great fanfare, everyone was left wondering who’d had the great idea.

watch He got a scholarship to Dartmouth and caught a lotta crap when he actually accepted it. That’s where he met Mom, and she waited for him while he took his turn in Vietnam. I have several faded pictures of him and his buddies strapped to the hilt with M-16s and bandolier type belts just crammed full of bullets. They’re sweating and laughing and slapping each other on the backs and holding up bottles of beer, cigarettes leering out of the corners of their mouths, packs rolled into their sleeves. But despite all that, Dad always said it wasn’t really like going to ‘Nam because he sat at some airbase and wrote copy for the US papers – never shot a single round, he said. I think he played it down, though. That’s just Dad.

http://www.mscnantes.org/ushmtxfsxar When he came home he talked his sweetheart into moving out to Oklahoma (the “wide-open country” he called it), they got married and had me, and soon thereafter Dad nursed Mom through the cancer that would take her away from us when I was only five. After that it was just the two of us. He came to my Brownie meetings and hosted my birthday parties and bought me my first bra and did all the stuff a mom usually does. And he did it without blinking, ‘cause that’s the sorta guy he is. Dad stayed a writer throughout his life, working at newspapers (which he left on principle if he felt too out of step with their editorial page) and writing novels in his spare time. He also played the mandolin and he liked to grow county fair-winning tomatoes and unusual eggplants, the egg shaped ones were his favorites. And he had this odd little habit of buying up anonymous old photographs which he said he used to spin his stories, looking at those immortalized faces, their futures laid out before them. “It could be anything,” he’d say, eyes far off, “anything at all could happen to them.” I think that alone gave him a powerful thrill, like some people feel when they contemplate their growing children’s futures, maybe.

Tramadol Online Prescription Uk While my devotion to Dad might be something more akin to hero worship, there are a few things I wish he’d done differently. For one, I wish he’d ventured his heart out more, maybe found himself someone to spend his life with after Mama. And I also wish he’d found himself some better representation so he could’ve made some actual money off of those dark Westerns he writes. They’re really good, but he sold them for a few hundred bucks each, sometimes a few thousand if the publisher felt moved by a bit of largess. I’m pretty sure that a famous Western writer you’ve all heard of “borrowed” a bit heavily from one of Dad’s stories…and Dad never did anything about it. But, as you know by now, that’s just Dad. And so help me, I’m awfully fond of the old guy.

Cheapest Place To Order Tramadol Online Funny, when you look at this picture of the four Miller Avenue Boys on their wagon-trike train, I guess it’s like Dad said about his hobby: Anything could’ve happened to them. Anything at all.

https://danivoiceovers.com/v4da9vp go site About The Author:

Heidi Kamm lives in Norman with her husband, son, and a dog that looks an awful lot like Santa’s Little Helper.

source url here About The Imaginary Family Project:

The 2011 Imaginary Family Project is a year-long collective art endeavor coordinated by occasional amateur artist Quentin Bomgardner and co-sponsored by The Red Dirt Chronicles. This project is based around “lost” vintage photographs, which have been acquired at flea markets, garage sales, estate sales, and eBay – heirloom collections, with no heir. Every week a different author will “find” one photograph by creating an imagined history around one of its subjects. At the end of the year, the collection will be compiled and presented as a group.

https://penielenv.com/nq2pl8qtb Previous Entry | Next Entry

Comments

https://paradiseperformingartscenter.com/mjknrronuq

https://getdarker.com/editorial/articles/cjgnm4rd8 Your story reflects both a specific era (my brothers’) and issues some men face today. Your story brought me into my own nostalgic feelings about my dad and brother, too! Thank you, Heidi. Beautifully done!

Order Tramadol Discount Hello, Heidi – great job with “The Miller Avenue Boys!” I liked your ‘dad’ character the best. He sounds just a teeny bit like my bro. ~ Red Dirt Kelly

Best Place Order Tramadol Online LOVE the pic…..and even more, your story that goes with it. We usually see those “old” pics and have to make up our own story. The real story may not always end like we want it to, but it makes you reflect for a moment, and wonder what one little thing could have changed the outcome. Thanks ♥